“It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world; so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it . . . .”

- George Washington

Now that Mubarak stepped down, many question the effects of the revolution on America’s standing in the region. The United States lost a staunch ally, and our past support for Mubarak may have ruined our reputation with the Egyptian people. Referring to the wisdom of our founding fathers may have helped us to avoid this foreign policy dilemma.

Washington would have opposed the United States’s alliance with Mubarak. But not necessarily for the reasons you would think.

Our first inclination would be to think Washington, the great soldier of liberty, would have been outraged that we were aligned with an authoritarian ruler who purportedly trampled the liberties of his people. And it is very true that he would have hoped the United States be a guiding light of freedom, he was more than a starry-eyed idealist. He was pragmatic.

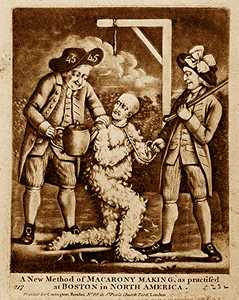

Washington won the war with the help of the French Monarchy. The Americans needed France’s help against the British onslaught and so Benjamin Franklin lobbied for aggressively for their aid. True, many Americans hated the idea of aligning themselves with an authoritarian regime. In fact, one of Benedict Arnold’s reasons for betraying the Revolutionary Cause was because he saw the alliance as a sure sign that the American cause had lost its way. But Washington knew he needed the kingdom’s supplies, troops, and navy to defeat the British. And he took them.

Washington likely would not have condemned working with Mubarak towards specific goals. Certainly American interests are at stake in the region, but not the fate of the country. But Washington would be frowned upon the depth of the relationship over the past decades. Washington saw alliances with regimes as a last resort to save the country rather than the “go to” method for pursuing all American interests. Further, he would likely opposed such interference with a foreign nation’s internal affairs. Washington likely would have avoided such intimacy with Mubarak, just like he did with the French after the American Revolution.

When the French declared war on the British again in 1789, President Washington remained neutral. He knew it was not in the United States’s interests to re-engage Britain in a bitter struggle. So even though his former allies were enraged, Washington refused to help. He declared America neutral and did everything in his power to avoid any “permanent alliances.”

I believe Washington’s inclination would be to focus more inwardly. Rather than entangling the nation with the regimes of the Middle East, Washington would likely adopt a much more “hands off” approach in which we would pursue American interests without taking sides, sending arms, deploying troops, or propping up governments. Acknowledging the need for temporary alliances, Washington would engage Egypt for specific tasks but would avoid the decades of entanglement that now threaten to ruin our relationship with the Egyptian people.

“Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none”

- Thomas Jefferson